North Pacific right whale

| North Pacific right whale[1] | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

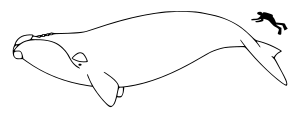

| Size comparison against an average human | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Balaenidae |

| Genus: | Eubalaena |

| Species: | E. japonica (Lacépède, 1818) |

| Binomial name | |

| Eubalaena japonica |

|

|

|

| Range map | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

The North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica) is a very large, robust baleen whale species that was common in the North Pacific until 1840, but now extremely rare due to 19th and 20th century whaling. There are apparently two populations of the species in the North Pacific. A population that occurs in the southeastern Bering Sea and eastern North Pacific may be 50 animals or less. A very poorly known population in the Sea of Okhotsk between the Kuril Islands and Sakhalin Island in Russia may number 300 or more animals, but there is almost no data on this population. Although the whales have been protected from whaling since 1935, illegal Soviet whaling in the 1950s and 60s depleted their numbers further. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature has expressed concern that its numbers are now too low for recovery, and that extinction may be inevitable. According to the Center for Biological Diversity, E. japonica is the most endangered whale on Earth.[3]

Contents |

Taxonomy

E. japonica is a member of the family Balaenidae, and all species of this family are often lumped together in popular accounts as "right whales". This family consists of two genera: Balaena—with one species, the bowhead whale of the arctic (B. mysticetus), and Eubalaena—the "right whales", also often called "black right whales". The much smaller pygmy right whale (Caperea marginata) of the Southern Hemisphere is considered to be in different family, Neobalaenidae.

Until recently, all right whales of the genus Eubalaena were considered a single species—E. glacialis. In 2000, genetic studies of right whales from the different ocean basins led scientists to conclude that the populations in the North Atlantic, North Pacific and Southern Hemisphere constitute three distinct species which they named: the North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis), the North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica) and the southern right whale (Eubalaena australis).[4] Further genetic analysis in 2005 using mitochondrial DNA and nuclear DNA has supported the conclusion that the three populations should be treated as separate species,[5] and the separation has been adopted for management purposes by the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service and the International Whaling Commission.[6]

Description

E. japonica is a very large, robust baleen whale. It very closely resembles the other right whale species—the North Atlantic right whale (E. glacialis) and the southern right whale (E. australis). Indeed, without knowing which ocean an individual came from, the physical similarities are so extensive that individuals can only be identified to species by genetic analysis.

E. japonica is easily distinguished in the wild from other whale species in the North Pacific. Right whales are very large and can reach 18.3 m (60 ft) in length, based on 20th century catch record, however, few animals can grow up even larger[7] and they are substantially larger than the gray or humpback whales. Right whales are also very stout, particularly when compared to the other large baleen whales such as the blue and fin whales. For 10 North Pacific right whales taken in the 1960s, their girth in front of the flippers was 0.73 of the total length of the whale.[8]

Right whales are the only baleen whale species in the North Pacific that lack a dorsal fin altogether. Right whales are also unique in that all individuals have callosities—roughened patches of epidermis covered with aggregations of hundreds of small cyamids that cluster on the callosities. As in other species of right whales, the callosities appear on its head immediately behind the blowholes, along the rostrum to the tip which often has a large callosity, referred to by whalers as the "bonnet".[8]

The species most similar to the North Pacific right whale in the North Pacific/Bering Sea area is the closely related bowhead whale. Both species have huge heads that constitute up to one-third of the body length, highly arched mouths, very long, fine baleen, no dorsal fin, and great breadth. However, the seasonal ranges of the two species do not overlap. The Bowhead Whale is found at the edge of the pack ice in more Arctic waters in the Chuckchi Sea and Beaufort Sea, and occurs in the Bering Sea only during winter. The bowhead whale is not found in the North Pacific. Bowhead whales completely lack callosities, the easiest way to distinguish the two species in photographs.

Although more than 15,000 right whales were killed by whalers in the North Pacific,[9], there are remarkably few detailed descriptions of these whales. Most of our information about the anatomy and morphology of E. japonica comes from 13 whales killed by Japanese whalers in the 1960s[10] and 10 whales killed by Russian whalers in the 1950s.[11] Basic information about right whale lengths and sex are also available from coastal whaling operations in the early part of the 20th century.[12]

Relative to the other right whale species, E. japonica may be slightly larger. The largest North Pacific right whale ever recorded was an 18.3 m (60 ft) female.[11] Like other baleen whales, female North Pacific right whales are larger than males. Brindle-colored individuals are less common than they are among the southern right whale.

Population

Historic population

Before being decimated by pelagic whalers in the mid-19th century, right whales were common in the North Pacific. The number of right whales killed in Japanese shore-based net whaling or by Native American whalers in the Aleutians was almost certainly so small that it did not reduce the overall population size. Accordingly, one can consider 1835 as a good year to use as a baseline for the historic population. In the single decade of 1840–49, between 21,000–30,000 right whales may have been killed in the North Pacific, Sea of Okhotsk and Bering Sea.[9] This suggests that right whales may have been as abundant as the Gray Whale in the North Pacific.

Current population

Southeastern Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska

Several writers have attempted to estimate the total population of right whales in the southeastern Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska, often referred to as the eastern North Pacific population. A comprehensive review of sighting data and population estimates in 2001 concluded that "none of the published estimates of abundance relating to North Pacific right whales can be regarded as reliable...[most] estimates appear to be little more than conjecture...[and] no quantitative data exist to confirm any of these estimates."[13]

All that can be said with any confidence is that as of 2004, there were at least 23 right whales in the southeast Bering Sea, since that number of whales were seen in two separate sightings in August.[6] From biopsy samples, it was determined that 10 were males and 7 females, and at least two of the whales were calves.[14] Prior to that sighting, extensive aerial and acoustic surveys in the southeastern Bering Sea and the Gulf of Alaska had not revealed more than six right whales in any year.[15] In 1998 and 2004 an individual right whale was seen in the Gulf of Alaska near Kodiak Island and right whale calls were recorded from this area in 2000.[16]

In a December 2006 status review of right whales, the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) stated: "Recent sightings suggest that the abundance in the eastern North Pacific is indeed very small, perhaps in the tens of animals." [6] The U.S. Marine Mammal Commission in its 2006 Annual Report stated that "the eastern population may now number no more than 50 individuals." [17] A 2008 report by researchers "the extreme rarity of sightings in recent decades suggests that the population numbers in the tens." [18]

The proposed oil and gas lease of North Aleutian Basin in the SE Bering Sea caused the Minerals Management Service (MMS) of the Department of the Interior to fund at an annual cost of about $1 million a cooperative series of annual surveys with the National Marine Fisheries Service and the North Pacific Research Board (NPRB), with a focus on located right whales and gathering further information about them. In 2007, from July 31 to August 28 an international team of scientists conducted shipboard surveys of an area almost the size of New York in search of Pacific right whales. "We did not see a single whale the entire time," said Phil Clapham, team leader and chief scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Alaska Fisheries Science Center in Seattle. "The bottom line, they were not in the places they had traditionally been in the last six or seven years" The research is required under the federal Endangered Species Act because the area where the whales like to spend summers overlaps an area the federal government in 2007 approved for oil and gas development. Lease sales could begin by 2011. The whales weren't found this summer because it is a "cold pool year" in the Bering Sea, Clapham said. That means the water is colder than normal. The colder water likely affected the distribution of plankton, which is what the large whales feed on, he said.[19]

In the summer 2008, follow-up aerial and shipboard surveys were conducted by NMFS (funded again by the MMS and the NPRB) 22 July – 31 August and 2 August – 12 September to investigate distribution, movements and ecology of right whales in the BS both in general as well as with respect to the planned oil lease. During these respective survey periods a total of 10 sightings (of 12 individuals) and 22 sightings (of 34 individuals) were recorded, respectively, including duplicate counts between platforms. All occurred within E. japonica critical habitat in the Bering Sea.

An Argos PTT satellite transmitter was deployed in one and the whale was monitored for 58 days, a period in which it remained in a relatively small area within the middle shelf of the Eastern Bering Sea, just to the north of the North Aleutian Basin. The number of whales photo-identified from ship and aerial surveys were 7–9 and 6, respectively, resulting in the identification of 9–11 ndividuals in total. The re-sighting rate of individuals was high for a whale population—four whales were seen by both survey platforms, indicating that a small number of individuals occurred in the survey area. Five whales seen in 2008 were also previously photographed in the Bering Sea in 1996–2002, and in 2004.[20] One of these individuals, identified as "Match 27" was a whale tagged in 2004.[21]

A 2010 study used photographic and genotype data to calculate the first mark–recapture estimates in the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands. The photographic data indicated a population of 31, while genotyping estimated 28. Of these eight were females and 20 males. Other data suggest that the total eastern North Pacific population is unlikely to be much larger. It is the world's smallest whale population for which an abundance estimate exists.[22]

Sea of Okhotsk

Pelagic whalers in the 19th century hunted large numbers of right whales along the coasts of Kamchatka and in the Sea of Okhotsk. The latter area is a large sea, ice covered most of the year, entirely in Russian waters. Due to Russia restrictions on access, little was known about whales in this sea. However, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Japanese research vessels in the Sea of Okhotsk reported 28 sightings of right whales in the Sea of Okhotsk. From this sample, the Japanese scientists estimated a population of 900 right whales in the Sea of Okhotsk, albeit with low confidence intervals (90% CI=400-2,100).[23] After a gap of 14 years, Japanese researchers were able to resurvey this area in 2005 and apparently saw similar numbers of right whales in the same area. Other scientists have disputed the methodology used to extrapolate a total population size, and contend that the population may be less than half of that.[13] However, it appears that there is a small population of right whales that summers in the Sea of Okhotsk. Where these whales go in winter is unknown.

Ecology and Behavior

Feeding

Like right whales in other oceans, E. japonicas feed primarily on copepods, mainly the species Calanus marshallae.[24] They also have been reported off Japan and in the Gulf of Alaska feeding on copepods of the genus Neocalanus with a small quantity of euphausiid larvae Euphausia pacifica.[6]

Like other right whale species, E. japonica feeds by skimming water continuously while swimming, in contrast to balaenopterid whales such as the blue and humpback whales which engulf prey in rapid lunges. Right whales do not have pleated throats. Instead they have very large heads and mouths that allows them to swim with their mouths open, the water with the copepods flowing in, then flowing sideways through the right whale's very long, very fine baleen trapping the copepods, and then out over their large lower lips.

It takes millions of the tiny copepods to provide the energy a right whale needs. Thus, right whales must find copepods at very high concentrations, greater than 3,000 per cubic meter to feed efficiently. National Marine Fisheries Service researchers mapped the southeast Bering Sea and the Gulf of Alaska for areas with sufficient productivity to support such concentrations and analyzed the roles of bathymetry and various gyres in concentrating copepods to such densities.[24]

Behavior

There have been very few, short visual observations of right whale behavior in the North Pacific. The mid-19th century whaling onslaught occurred before there was much scientific interest in whale behavior, and included no scientific observation. By the time scientific interest in this species developed, few whales remained and nowhere in the eastern North Pacific or Bering Sea could observers reliably find them. As of 2006, scientists had had minimal success satellite tagging North Pacific right whales.[14] Observations total probably less than 50 hours over the last 50 years. What little is known about North Pacific right whale behavior suggests that it is similar to the behavior of right whales in other oceans, except in its choice of wintering grounds. The individual which was observed during a whale-watching tour off Kii Peninsula, Japan repeated breach six times in a row.[25]

There have been some noteworthy non-visual observations. NMFS biologists deployed various passive acoustic listening devices in the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska, recording at least 3,600 North Pacific right whale calls between 2000–2006. Nearly all of these calls came from the shallow shelf waters at approximately 70 meters (230 ft) of the southeastern Bering Sea in what is now designated Critical Habitat for this species. 80% were frequency-modulated "up-calls" at an average 90–150 Hz and 0.7 second duration. "Down-up" calls constituted about 5% of the calls, and swept down for 10–20 Mz before becoming a typical "up-call". Other call types, e.g. downsweeps and constant-tonal "moans" constituted less than 10% of total calls. The calls were clumped temporally—apparently involving some level of social interaction, as has been found in the calls of right whales in other oceans. The calls came more at night than during the day.

The very small number of North Pacific right whale calls detected during the NMFS research—hundreds per year contrast with the vastly greater number (hundreds of thousands) of bowhead whale calls during migration in the western Arctic and blue whale calls off California—further reinforces the conclusion that the population size of North Pacific right whales in the Bering Sea is very small.[26]

Range and habitat

Historic

Before 1840, its range was extensive and had probably remained the same for at least hundreds of years. It ranged from the Sea of Okhotsk to the western coast of Canada. The seasonal movements and the densest concentrations of whales, then as now, are unknown.

To determine where the right whales were, an imaginative cooperation developed between whalers and one of the U.S.'s first oceanographers. In the 1840s the principal mariners who ventured away from the main trade routes were whalers. The description of currents, winds, and tides in these remote regions was of great interest to the U.S. Navy. Accordingly, Naval Captain Matthew Fontaine Maury made a deal with whalers. If they provided him with their logbooks, from which he could extract wind and current information, he would in return prepare maps for them showing where whales were most concentrated. Between 1840–1843, Maury and his staff processed over 2,000 whaling logbooks and produced not only the famous Wind and Current Charts used by mariners for over a century, but also a series of Whale Charts. The most detailed showed by month and 5° of latitude and longitude: (a) the number of days on which whaling ships were in that sector; (b) the number of days on which they saw right whales; and (c) the number of days on which the saw sperm whales. In the North Pacific, these charts summarize more than 8,000 days on which the whalers encountered right whales and the searching effort by month and sector. The maps thus provide a crude measure of the relative abundance of right whales by geographic sector and month, controlled for the very non-random searching effort of the whalers.

North Pacific whalers hunted mainly in the summer, and that is reflected in the Maury Whale Charts. There were almost no winter sightings and very few south of 20°N. The densest concentrations occurred along both coasts of Kamchatka and in the Gulf of Alaska.[27]

In 1935, Charles Townsend from the New York Zoological Society (now the Wildlife Conservation Society) reviewed 2,000 whaling logbooks and mapped the locations of whale taken by species. His Chart C[28] shows catch locations around the world, including the location by month of most of the 2,118 right whales taken in the North Pacific between 1839–1909, using data copied from 249 logbooks. His charts do not adjust for the nonrandom distribution of whalers, so they are biased by the whalers' preference for more coastal, more protected, and closer waters. s Chart C shows three main concentrations of right whales—one in the Gulf of Alaska; one along Kamchatka and the Sea of Ohotsk; and another in the Sea of Japan.[27][29]

Of particular interest are the questions of how many "stocks" of right whales exist in the North Pacific. Was there just a single population across the North Pacific? Was there an eastern population that summered in the Gulf of Alaska and a second population in the western North Pacific. Was the population in the Sea of Ohotsk a third population distinct from the whales found in the Pacific east of Kamchatka?

Recently, researchers reanalyzed this early whaling data, along with more recent but much sparser recent sighting data. They conclude that there are probably at least two stocks of right whales in the western and eastern North Pacific, but that it was still unclear whether the Okhotsk population was a separate stock.[24][30]

E. japonica's distribution is more temperate than that of the more polar Bowhead whale, and there are no records of the two species inhabiting the same area at the same time. E. japonica's summer distribution extends north into the southeastern part of the Bering Sea. In summer, the Bowhead migrates north through the Bering Straits and is in the Chukchi Sea and Beaufort Sea. In winter, the ice-loving Bowhead moves south into the Bering Sea, but the right whales have migrated further south of the Aleutian Islands into the North Pacific.

Modern

Bering Sea & eastern North Pacific

Despite many aircraft and ship-based searches,[31] as well as analysis of listening device records, only a few small areas report recent sightings in the eastern North Pacific. The southeastern Bering Sea produced the most, followed by the Gulf of Alaska, and then California. In 2000, 71 calls were recorded by a deep-water passive acoustic site at 53° N 157° W. An additional 10 were recorded near Kodiak Island in the Gulf of Alaska at 57°N 152°W[32] In 2004, a group of two were seen in Bering Sea on August 10. Another of 17 including two calves was noted in September, and one in Gulf of Alaska.[14] In 2005, 12 right whales were seen in October just north of Unimak Pass.[6]

Review of more than 3,600 North Pacific right whale calls detected by passive listening devices between 2000–2006 strongly suggests that the whales migrate into the southeast Bering Sea (presumably from the North Pacific) in late spring and remain until late fall. The earliest were in late May and the latest in December. The peak calling period was July through October. Most were detected from shallow shelf sites within the designated Critical Habitat area. From October through December 2005, several calls were detected at the northwestern middle-shelf and the deeper shelf sites, suggesting that they may appear at different seasons and during migration.[26]

Western North Pacific and Sea of Okhotsk

There are very few reports of right whales in the western North Pacific.

There appears to be a remnant population in the Sea of Okhotsk, along with remnant populations of the eastern stock of Gray and Bowhead whales. The distribution of these three species is quite different. In summer the Bowheads inhabit the northwestern corner of the Sea of Okhotsk. The Gray Whales stay close to Sakhalin Island, near massive new energy developments. In contrast, the right whales inhabit the southern Sea of Okhotsk nearer the Kuril Islands and northeast of Sakhalin Island. This area's remoteness makes observation very difficult and expensive.

Based on survey records from "JARPN" and "JARPN II" conducted by Institute of Cetacean Research, right whales were distribured mainly in offshore waters from 1994 to 2007.[33] While total of 40 animals with 28 schools were recorded, there were 6 cow-calf pairs during the period.

Migration and winter range

Large fractions of the other right whale species winter close to shore. However, no coastal or other wintering ground has been found for north Pacific right whales.[27][30]

Some right whales still migrate south along Japan's coasts particularly the Pacific side of northern Japan. Japanese whale research surveys found one right whale off the southern coast of Koshiro, Hokkaido in September 2002,[34] and one right while off the Pacific coast of Honshu Japan in April 2003.[35] What portion of the migration passes southern Japan is unknown, and the number of records is small.[36][37] There are at least two records in spring-summer 2006 off the coast of Kii Peninsula, one of the major historical whaling grounds.[38] There is also a record of an adult escaping from a fishing net near Taiji Town in January 2009.[39][40] A short Japanese video is available.[41]

Two adults stranded in northern and southern Ibaraki Prefecture in 2003[42] and 2009[43]. The whales may have wintered in the Bonin Islands, but few sightings in recent decades support this idea.[44] Two animals appeared just off Mikura island in March, 2008.[45]

Modern sightings in the Japan Sea, East and South China Seas, and Yellow Sea are rare.[46] Historically, right whales may have wintered in East China Sea from Ryukyu Islands to south of China including Taiwan though there is little scientific evidence supporting this idea. Only a few confirmed sightings in the area have occurred since the 1950s, including one from Amami Oshima in April, 1997.[47]

Until recently, most researchers thought that right whales in the eastern North Pacific wintered off the west coast of North America, particularly along the coasts of Washington, Oregon and California. There have been a few winter sightings in all these areas, particularly in California. However, a more detailed study argues that these single individuals were merely stragglers. Notwithstanding 7 days/week whale-watching operations in several parts of this range, there have been only 17 sightings between Baja and Washington state.[48] The absence of calves from historic California stranding data suggests that this area was never an important calving or wintering ground.[49]

Threats

So little is known about North Pacific right whales that any description of the threats they face necessarily involves some speculation. Much more is known about the threats faced by North Atlantic right whales, so a review of those threats is a good place to start.

Unsustainably small population

When populations of wild animals get very small, the population becomes much more vulnerable to certain risks than larger populations. One of these risks is inbreeding depression.[6]

A second risk of very small populations is their vulnerability to adverse events. In its 2006 Status Review, NMFS stated E. japonica's low reproductive rates, delayed sexual maturity, and reliance on high juvenile survivorship combined with its specialized feeding requirements of dense schools of copepods "make it extremely vulnerable to environmental variation and demographic stochasticity at such low numbers".[6] For example, a localized food shortage for one or more years may reduce the population below a minimum size. As the NMFS Status Review notes: "Zooplankton abundance and density in the Bering Sea has been shown to be highly variable, affected by climate, weather, and ocean processes and in particular ice extent."[6]

A third risk is mating. With so few whales in such a large area, simply finding a mate is difficult. Right whales generally travel alone or in very small groups. In other oceans, breeding females attract mates by calling. The success of this strategy depends upon having males within hearing range. As expanding shipping traffic increases the ocean's background noise, the audible range for such mating calls has decreased.

Oil exploration, extraction, transport and spills

Energy production in the right whale's range creates the threat of oil spills. In 2005 the wreck of the M/V Selendang Ayu near Unalaska released approximately 321,000 US gallons (7,400 imp bbl) gallons of fuel oil and 15,000 US gallons (350 imp bbl) of diesel into the Bering Sea.

The for new oil and natural gas fields and their subsequent development and operation involves several threats to right whale survival. In its 2006 Status Review, NMFS notes that the development of the Russian oil fields off the Sakhalin Islands in the Sea of Okhotsk "is occurring within the habitat" of the western population of North Pacific right whales.[6]

On April 8, 2008, a NMFS review found that there had been no recent Outer Continental Shelf oil and gas activities in or adjacent to the areas designated as critical habitat for E. japonica.[50] However, on the same day the U.S. Minerals Management Service (MMS) published a notice of a proposed Oil and Gas Lease Sale 214 for 5,600,000 acres (23,000 km2) in the North Aleutian Basin. MMS announced the beginning of preparation of an environmental impact statement for this lease. If leasing proceeds, the sale would occur in 2011 and exploratory drilling could begin in 2012.[51] More than half of the lease area is within the designated critical habitat of the North Pacific right whale.[52] The Center for Biological Diversity is suing to shut down the sale.[53]

The exploration phase is characterized by numerous ships engaged in seismic testing to map undersea geological formations. Testing involves blasts of noise which echo off the undersea rock formations. These explosions have been banned in the Beaufort Sea during the time of year that bowheads are present. In its 2006 Status Review, NMFS concludes: "In general, the impact of noise from shipping or industrial activities on the communication, behavior and distribution of right whales remains unknown."[6]

Environmental changes

The habitat of E. japonica is changing in ways that threaten its survival. Two environmental effects of particular concern are global warming and pollution.

The high densities of copepods that right whales require for normal feeding are the result of high phytoplankton productivity and currents which aggregate the copepods. Satellite studies of right whales show them traveling considerable distances to find these localized copepod concentrations.

Global warming can affect both copepod population levels and the oceanographic conditions which concentrate them. This ecological relationship has been studied intensively in the western North Atlantic.

Entanglement in fishing gear

Unlike in the North Atlantic there is no record of entanglement in the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska. However, in the eastern Bering Sea gear is deployed in nearshore waters, areas "not associated and generally not overlapping with known North Pacific right whale distribution." Pot fisheries occur in offshore waters, but are often deployed in winter when right whales are not known to be present.[6]

In the Sea of Okhotsk entanglement in fishing gear may be a significant problem. Deep-water crab traps and Japanese pelagic driftnet gear for salmon. Right whales have been found: alive but entangled in or wounded by crab net gear (2003 and 1996), dead from entanglement in unspecified gear (September 1995), dead from entanglement in Japanese drift net (October 1994), and alive with fishing gear wrapped on the tail flukes (August 1992).[13][54]

Ship collisions

Collisions with commercial ships is the greatest threat to North Atlantic right whales. Both summer feeding ranges and winter calving grounds are located in busy shipping channels.[6] However, E. japonica does not frequent shipping channels. There is almost no published data that identifies or quantifies ship collisions or entanglement as substantial mortality factors for them.[6]

Ship noise

In its 2006 Status Review, NMFS reviews the scientific studies on the effects of noise pollution on marine mammals and concludes: "In general, the impact of noise from shipping or industrial activities on the communication, behavior and distribution of right whales remains unknown."[6]

Whaling

Whaling no longer threatens E. japonica. However, Between 1963 and 2001, Soviet whalers illegally killed 498, dramatically increasing extinction risk. In the 1970s, four were taken by Chinese and Korean whalers. However, there is no later record of targeting right whales.[13]

Conservation

Finding right whales

The threshold problem for conserving this species is locating them. While the other right whale species appear predictably along their migration routes,[55] there are no locations where E. japonica can reliably be found. The Sea of Okhotsk may be an exception, but its remoteness has prevented a thorough assessment.

The species is so rare that NMFS has had only intermittent success in locating them in the southeast Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska. Small numbers were located in the Bering Sea in 1966[56] and 1997–2004.[31][57]. However, a month of dedicated research cruises in August 2007 sighted no right whales. This tiny population was elsewhere.[58]

In winter, their location is particularly mysterious. There have been a few sightings in California and even Baja, particularly in the 1990s. However, they have been rare and of short duration.[59]

In the Sea of Okhotsk, they appear far from shore in the southern part of the sea. The Sea is all Russian territorial waters, so Russian cooperation is required for any surveys. The remoteness of the location and the enormous demand for ships and aircraft associated with oil and gas exploration near Sakhalin Island, would make any ship or aerial surveys difficult and expensive.

One technology that holds promise for finding right whales is passive acoustic listening. Such devices record for hundreds of hours. The technology is able to detect submerged animals, independent of water clarity.[60][61]

Another, expensive technology that can provide information about this species are satellite-monitored radio tags. These are non-lethal, and applied with a crossbow, can beam the whales' location, movements, dives and other information to researchers. The technique has been used successfully in the North Atlantic. The challenge is to bring the tag and the right whale together.

Acoustic detection and satellite tags can work together. In August 2004, NMFS listening devices in the southeastern Bering Sea detected right whale vocalizations. The researchers then deployed directional and ranging sonobuoys to locate the calling whales. This information allowed researchers to photograph and tag two right whales, and obtain genetic samples. Only one tag worked, and it failed after 40 days, just as the whale was expected to start its southern migration. During that period the whale moved throughout a large part of the shelf, including areas of the outer shelf where right whales have not been seen in decades.[14]

International law

The right whale's plight was recognized relatively early. Hunting them was prohibited in the first international whaling treaty, the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling signed in 1931. The treaty came into effect in 1935. Although the United States, Canada and Mexico ratified the treaty, Japan and the Soviet Union did not, and thus were not bound by it. Attempts to bring the other major whaling nations under an international regime stalled until after World War II.[62]

In 1946 the major whaling countries signed the Convention on the International Regulation of Whaling which established the International Whaling Commission (IWC) and took effect in 1949. The Commission's initial regulations barred whaling of right whales. Currently, the IWC classifies E. japonica a "Protection Stock" banning commercial whaling.[63]

The International Whaling Commission sets maximum annual quotas for "commercial" whaling—zero in the case of right whales. However, the underlying Convention explicitly authorized member countries to issue permits to take whales for scientific research.[64] This exemption/loophole has recently become a heated, controversial subject as Japan has been testing the catch limits and the definition of scientific research, justifying such catches in the absence of a commercial quota. In 1955, the Soviet Union granted permits to kill 10 right whales, and in 1956 and 1958 the Japanese granted permits to kill 13 right whales. These 23 animals provided most published morphology and reproductive biology data. No further right whale permits have been issued by any country.[62]

During the 1960s, the International Whaling Commission did not place observers on whaling ships. Whaling nations were expected to monitor their whalers. The Soviet Union abused this process, directing its whalers to capture thousands of protected Blue Whales, Humpback Whales and right whales around the world.

All right whales (Eubalaena spp.) are listed in CITES Appendix I.[65], which bans commercial trade.

United States laws and regulations

The Whaling Convention Act[66] implements the ban on hunting right whales. The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) of the Department of Commerce has jurisdiction.

Under the Endangered Species Act, E. japonicas is listed as "endangered".[67] Under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, all right whales, including E. japonica, were determined to be "depleted" in 1973 and remain so classified.

Critical habitat

History

On 4 October 2000, the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD) petitioned NMFS to designate the southeast Bering Sea shelf from 55–60°N as critical habitat for E. japonica. On 20 February 2002, NMFS declined (67 FR 7660) at that time, arguing that available information was insufficient for such a finding. CBD challenged NMFS in court, and in June 2005, a federal judge directed the agency to make a designation. In 2006, NMFS complied, designating one in the Gulf of Alaska south of Kodiak Island and one in the southeast Bering Sea (71 FR 38277, 6 July 2006). Later, NMFS split the "northern right whale" into E. glacialis and E. japonica, and reissued its rule.[68][69]

Rationale

Critical habitats must contain one or more "primary constituent elements" (PCEs) that are essential to the conservation of the species.[70] NMFS identified as PCEs:

- species of large zooplankton in right whale feeding areas, in particular the copepods Calanus marshallae, Neocalanus cristatus, and Thysanoessa raschii whose high lipid content and occurrence make them preferred prey items.[71]

- physical concentrating mechanisms, physical and biological features that aggregate prey into densities high enough to support efficient feeding.[72]

NMFS simply used repeated right whale sightings in the same small area in spring and summer as a proxy for the presumed PCEs.

Conservation impact

These areas support extensive and multi-species commercial fisheries for pollock, flatfish, cod, various crabs and other resources (but not salmon). NMFS ruled that these fisheries do not threaten PCE availability. NMFS also ruled that the zooplankton PCE was vulnerable to oil spills and discharges, which may require measures such as conditioning federal permits or authorizations with special operational constraints.[72]

Once a critical habitat has been designated, federal agencies must consult with NMFS to ensure that any action they authorize, fund or carry out is unlikely to destroy or adversely modify it.

Recovery plans

NMFS adopted a Final Recovery Plan for the North Atlantic right whale, but not for E. japonica. NMFS created a Northern right whale Recovery Team in July 1987. After public review of a Draft Recovery Plan, in December 1991, NMFS approved the Final Recovery Plan for the Northern right whale (including both the North Atlantic and North Pacific right whales). (The factors affecting the continued survival of the Northern right whale identified in that plan are discussed above in the section on threats to the continued survival of E. japonicas)

After the species split, NMFS revised its plan, limiting it to the North Atlantic right whale.[73] NMFS is developing a separate recovery for the North Pacific right whale.[74] issuing a status review in December 2006.[75]

Canadian regulation

In Canada, some right whales had been caught in the early 20th century from whaling stations off northern Vancouver Island. However, there have been no sightings of right whales in Canadian waters since the large illegal Soviet kill in the 1960s, much of which took place in the eastern Bering Sea. Nevertheless, in 2003, Fisheries & Oceans Canada issued a National Recovery Strategy for E. japonica in Pacific Canadian Waters, followed, in February 2007, by a draft plan.[76]

History

Artisanal and early pelagic: Pre–1835

In Japan, hunting for right whales dates back at least to the 16th century, although stranded whales had been utilized for centuries before then. In 1675, Yoriharu Wada invented a new method of whaling, entangling the animals in nets before harpooning them. Initially the nets were made of straw, later replaced by the stronger hemp. A hunting group consisted of 15–20 Seko-bune or "beater" boats, 6 Ami-bune or netting boats and 4 Mosso-bune or tug boats, for a total of 30–35 boats with crews totaling about 400. In addition to right whales, they took Gray Whales and Humpback Whales.[44]

Hunts took place in two regions: the south coast (Mie, Wakayama and Kochi prefectures) on the east coasts, and the waters north of the prefectures from Kyoto to Yamaguchi and to the west of Kyushu which hunted in the Sea of Japan. Off the south coast of Japan, hunting lasted from winter to spring. Catches in Kochi prefecture between 1800–1835 totaled 259 whales. Catches at Ine on the Sea of Japan during the periods 1700–1850 averaged less than 1 per year. Catches at Kawaijiri also on the Sea of Japan averaged 2 per year from 1699–1818.[44]

A few Native American tribes hunted in the North Pacific. Their catches were much lower than the Japanese. The Inuit along the western and northwestern coasts of Alaska have hunted whales for centuries. However, they prefer the Bowhead Whale, and occasionally the Gray Whale. They hunted at or beyond the northern limits of the right whale's range.

Aleuts hunted E. japonica and Gray whales along the Aleutian Islands and the Alaska peninsula, using poisoned harpoons. The catch was not recorded, but is unlikely to be more than a few per year.[49][77]

The Nootka, Makah, Quilleute and Auinault tribes of Vancouver Island and the coast of Washington were also skilled whalers of the Gray and humpback Whales. Right whales were rare in their catches.[49]

The North Pacific was the furthest from New England and Europe markets. During the open-boat whaling era, the mainly American ships hunted in the nearest ranges first. As the fleet grew, boats spread to the eastern North Atlantic and, by the 1770s, the South Atlantic. Following the lead of the British, American vessels first sailed the South Pacific in 1791, and by the end of the decade had reached the eastern North Pacific. By the 1820s, the whalers had started to use Lahaina, Hawaii as a base for hunting Sperm Whales.

Pelagic: 1835–1850

In 1835, the French whaleship Gange ventured north of 50°N and became the first pelagic whaler to catch a North Pacific right whale. Word quickly spread. Whaleships north of 50° increased from 2 in 1839 to 108 in 1843 and 292 in 1846. At its height, approximately 10% of the fleet was non-American, primarily French.[27][78]

It has been estimated that the total catch in this fishery was 26,500–37,000 animals during the period 1839–1909, concentrated in the single decade of 1840–49, which included about 80% of the total.[9]

In 1848, a whaler ventured through the Bering Straits and discovered unexploited populations of Bowhead Whales. Being more abundant, easier to capture, and yielding far more baleen, the majority of whalers rapidly switched to hunting Bowheads. Since Bowheads range further north than right whales, hunting pressure on right whales declined rapidly.[78]

Industrial: 1850–1960s

In the decade between 1850–1859, the catch dropped to 3,000–4,000 animals, one-sixth the previous level. Between 1860–1870, it dropped to 1,000 animals. By the end of the 19th century, pelagic whalers averaged less than 10 right whales per year.[9]

In the late 19th century, steam propulsion and the explosive harpoon opened up new whaling opportunities. Species previously too swift to hunt commercially could now be caught—Blue and Fin Whales. Small coastal whaling operations opened in California, Oregon, and Washington, British Columbia, and in the Aleutian Islands and in southeast Alaska, and in the Kuril Islands in the west. Whalers hunted by day, towing their catch to shore for flensing, operating in a fairly small area around the whaling stations. Although they weren't the primary targets, a few right whales were recorded in catches from these stations.[13][49][78][79] A close-up photo of a North Pacific right whale taken at the Kyuquot whaling station, British Columbia in 1918 can be seen here.

The later "factory ships" that processed carcasses while at sea further transformed pelagic whaling. Right whales continued to be taken, although uncommonly due to their rarity. Japan continued hunting right whales through the beginning of World War II. Afterwards, General Douglas MacArthur, head of Allied occupation forces, encouraged the Japanese to resume whaling to feed their hungry population. However, Japan then joined the International Whaling Commission which barred the hunting of right whales. Except for 13 killed under "scientific permits", in accordance with IWC rules, Japanese whalers have honored this prohibition.

Illegal Soviet: 1960s

The same cannot be said for Soviet whalers. In the 1960s, Soviet whalers had no international observers on board, and no conservation groups following them at sea. The Soviet whalers apparently honored the prohibition on taking right whales until 1963, by which time populations of humpback, blue and fin whales were getting harder to find in the North Pacific. Between 1963–67, the Soviet whalers ignored the ban on hunting right whales, apparently killed every right whale they found, and then filed fraudulent reports with the Bureau of International Whaling Statistics and the International Whaling Commission. During these five years, the Soviets killed 372 right whales in the Bering Sea and eastern North Pacific, an additional 126 right whales in the Sea of Okhotsk between 1963–67 and another 10 more in the Kuril Islands in 1971. In their reports, the Soviets admitted killing only one right whale, by accident. The Russian biologists who had been on the whaling ships were prohibited from examining the carcasses or taking any biological measurements of these whales. Nevertheless, the biologists kept their own records of what the whalers actually caught, then kept these records secret for more than two decades.[80] After the collapse of the Soviet government, the new Russian government released the true catch data.[13]

References

- ↑ Mead, James G.; Brownell, Robert L., Jr. (16 November 2005). "Order Cetacea (pp. 723-743)". In Wilson, Don E., and Reeder, DeeAnn M., eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2 vols. (2142 pp.). ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=14300009.

- ↑ Reilly, S.B., Bannister, J.L., Best, P.B., Brown, M., Brownell Jr., R.L., Butterworth, D.S., Clapham, P.J., Cooke, J., Donovan, G.P., Urbán, J. & Zerbini, A.N. (2008). Eubalaena japonica. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 7 October 2008.

- ↑ North Pacific right whale, Center for Biological Diversity.

- ↑ H. C. Rosenbaum, R. L. Brownwell Jr, M. W. Brown, C. Schaeff, V. Portway, B. N. White, S. Malik, L. A. Pastene, N. J. Patenaude, C. S. Baker, M. Goto, P. B. Best, P. J. Clapham, P. Hamilton, M. Moore, R. Payne, V. Rowntree, C. T. Tynan, J. L. Bannister & R. DeSalle (2000). "World-wide genetic differentiation of Eubalaena: questioning the number of right whale species". Molecular Ecology 9 (11): 1793–1802.

- ↑ Gaines, C.A., M.P. Hare, S.E. Beck and H.C. Rosenbaum (2005). "Nuclear markers confirm taxonomic status and relationships among highly endangered and closely related right whale species". Proc. R. Soc. B 272: 533–42.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 NMFS (National Marine Fisheries Service). 2006. Status Review: right whales in the North Atlantic and North Pacific Oceans.

- ↑ http://pubs.aina.ucalgary.ca/arctic/Arctic39-1-43.pdf

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Reeves RR and Brownell RL (1982). "Baleen Whales – Eubalaena glacialis and Allies". In eds. Chapman JA and Feldhammer GA. Wild Mammals of North America – Biology, Management, Economics. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 415–444. ISBN 0-018-2353-6.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Scarff JE (2001). "Preliminary estimates of whaling-induced mortality in the 19th century Pacific northern right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) fishery, adjusting for struck-but-lost whales and non-American whaling". J. Cetacean Res. Manage (Special Issue 2): 261–268.

- ↑ Omura H (1958). "North Pacific right whale". Sci. rep. Whales Res. Inst., Tokyo 13: 1–52.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Klumov SK (1962). "Gladkie (Yaponskie) kity Tikhago Okeana (The right whales in the Pacific Ocean)". Tr. Inst. Okeanol. Akad Nauk SSR 58: 202–97.

- ↑ Brueggemann JJ, Newby T, and Grotefendt RA (43–46). "Catch records of twenty North Pacific right whales from two Alaska whaling stations, 1917–1939". Arctic 39 (1).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Brownell RL Jr., Clapham PJ, Miyashita T, and Kasuya T (2001). "Conservation status of North Pacific right whales". J. Cetacean Res. Manage. (special issue 2): 269–286.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Wade P, Heide-Jørgensen MP, Shelden K, Barlow J, Carretta J, Durban J, LeDuc R, Munger L, Rankin S, Sauter A, Stinchcomb C (2006). "Acoustic detection and satellite-tracking leads to discovery of rare concentration of endangered North Pacific right whales". Biol. Lett. 2: 417–419.

- ↑ http://www.sfcelticmusic.com/js/RTWHALES/nprightw.htm#Sightings%20or%20Recordings

- ↑ 73 F.R. 19006

- ↑ Marine Mammal Commission, Annual Report for 2006 at 66.

- ↑ Alexandre N. Zerbini, et al. 2008. Occurrence of the Endangered North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica) in the Bering Sea in 2008 (poster on NMFS website – retrieved July 9, 2009

- ↑ "Endangered right whale Remains Elusive – Scientists Surveying Bering Sea Fail To Spot A Single Pacific right whale" – CBS News October 11, 2007.

- ↑ NMFSsurvey2008

- ↑ http://iwcoffice.org/_documents/sci_com/sc61docs/SC-61-BRG16.pdf

- ↑ Wade, Paul R.; Kennedy, Amy; LeDuc, Rick; Barlow, Jay; Carretta, Jim; Shelden, Kim; Perryman, Wayne; Pitman, Robert et al. (June 30, 2010). The world's smallest whale population?. Biology Letters. doi:10.1098.

- ↑ Miyashita T, and Kato H. 2001. Recent data on the status of right whales in the NW Pacific Ocean. Report of the International Whaling Commission. SC/M98/RW11.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Sheldon KE, Moore SE, Waite JM, Wade PR, and Rugh DJ (2005). "Historic and current habitat use by North Pacific right whales Eubalaena japonica in the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska". Mammal Rev. 35 (2): 129–155.

- ↑ http://www.nanki-marin.net/

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Munger LM, Wiggins SM, Moore SE, and Hildebrand JA (2006). "North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica) seasonal and diel calling patterns from long-term acoustic recordings in the southeastern Bering Sea, 2000–2006". Marine Mammal Science 24 (4): 174–7692.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Scarff JE (1991). "Historic distribution and abundance of the right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) in the North Pacific, Bering Sea, Sea of Okhotsk and Sea of Japan from the Maury Whale Charts". Rep. Intl Whal. Commn 19 (1): 1–50.

- ↑ Chart C

- ↑ Townsend CH (1935). "The distribution of certain whales as shown by logbook records of American whaleships" (PDF). Zoologica 19 (1): 1–50. http://www.wcs.org/media/file/zoologica19%281%29.pdf. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Clapham PJ, Good C, Quinn SE, Reeves RR, Scarff JE, and Brownell RL Jr. (2004). "Distribution of North Pacific right whales (Eubalaena japonica) as shown by 19th and 20th century whaling catch and sighting records". J. Cetacean Res. Manage 6 (1): 1–6.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 LeDuc RG, Perryman WL, Gilpatrick JW Jr, Hyde J, Stinchcomb C, Carretta JV, and Brownell RL Jr (2001). "A note on recent surveys for right whales in the southeastern Bering Sea". J. Cetacean Res. Manage (Special Issue 2): 287–289.

- ↑ Mellinger DK, Stafford KM, Moore SE, Munger L, and Fox CG (2004). "Detection of North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica) calls in the Gulf of Alaska". Marine Mammal Science 20: 872–879.

- ↑ http://www.iwcoffice.org/_documents/sci_com/workshops/SC-J09-JRdoc/SC-J09-JR35.pdf

- ↑ http://iwcoffice.org/_documents/sci_com/workshops/MSYR/SC-55-O8.pdf

- ↑ http://www.iwcoffice.co.uk/_documents/sci_com/workshops/MSYR/SC-56-O14.pdf

- ↑ http://icrwhale.org/zasho3.htm

- ↑ http://svrsh2.kahaku.go.jp/drift/FMPro

- ↑ http://minamikisyu.i-kumano.net/news/2006_05/20060517_00.htm

- ↑ http://svrsh1.kahaku.go.jp/m/mm/?p=1714

- ↑ http://minamikisyu.i-kumano.net/news/2009_01/20090120_00.htm

- ↑ http://km-world.tv/topic_news/kumano_news_001.html

- ↑ http://svrsh1.kahaku.go.jp/m/mm/?p=152

- ↑ http://icrwhale.org/stranding0901.htm

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Omura H (1986). "History of right whale catches in the water around Japan". Rep. Int. Whal. Commn. (Special Issue 10): 35–41.

- ↑ http://svrsh2.kahaku.go.jp/drift/FMPro?-db=rec2000web.fp5&-format=%2fdrift%2fe%2fsearch%5fresults.htm&-lay=hp&-sortfield=date8&-sortorder=descend&%8e%edid=006&-format=/drift/E/record_detail.htm&-skip=16&-max=1&-find

- ↑ http://svrsh2.kahaku.go.jp/drift/FMPro?-db=rec2000web.fp5&-lay=hp&-format=/drift/e/search_results.htm&-error=/drift/e/search_error.htm&種id=006&-SortField=Date8&-Sortorder=Descend&-Find

- ↑ http://svrsh2.kahaku.go.jp/drift/FMPro?-db=rec2000web.fp5&-format=%2fdrift%2fe%2fresults.htm&-lay=hp&-sortfield=%90%bc%97%ef%94%4e%8c%8e%93%fa&sp%5fid=6&-format=/drift/e/detail.htm&-skip=6&-max=1&-find

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 Scarff JE (1986a). "Historic and present distribution of the right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) in the eastern North Pacific south of 50°N and east of 180°W.". Rep. int. Whal. Commn (special issue 10): 43–63.

- ↑ 73 F.R. 19009

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ map

- ↑ Center for Biological Diversity press release, April 8, 2008 Retrieved – November 12, 2008

- ↑ Burdin AM, Nikulin VS and Brownell RL Jr (2004). "Cases of entanglement of western north-pacific right whales (Eubalaena japonica) in fishing gear: serious threat for species survival". In ed. Belkovich VM (PDF). Marine Mammals of the Holarctic. KMK Moscow. pp. 95–97. http://2mn.org/downloads/bookshelf/mm3_book/72-132.pdf. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ↑ Chadwick DH and Skerry B (2008). "right whales on the brink on the rebound". National Geographic 214 (4): 100–121. http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2008/10/right-whales/chadwick-text.

- ↑ Goddard, PC and Rugh, DJ (1998). "A group of right whales seen in the Bering Sea in July 1996.". Mar. Mammal Sci. 14 (2): 344–399. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/119942751/abstract.

- ↑ Waite JM, Wynne K, and Mellinger DK (2003). "Documented sightings of North Pacific right whale in the Gulf of Alaska and post-sighting acoustic monitoring". Northwestern Naturalist 84: 38–43. http://www.jstor.org/pss/3536721.

- ↑ Pemberton, Mary. "Endangered right whale remains elusive". CBS News. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2007/10/11/tech/main3357927.shtml. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ↑ North Pacific right whales – The Forgotten Species

- ↑ McDonald MA and Moore SE (2002). "Calls recorded from North Pacific right whales (Eubalaena japonica) in the eastern Bering Sea". J. Cetacean Res. Manage 4: 261–266.

- ↑ Mellinger DK, Stafford KM, Moore SE, Munger L, and Fox CG (2004). "Detection of North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica) calls in the Gulf of Alaska". Mar. Mammal Sci. 20: 872–879.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Scarff JE (1977). "The international management of whales, dolphins, and porpoises, an interdisciplinary assessment". Ecol. Law Quart. 6: 323–427, 574–638.

- ↑ International Whaling Commission, Schedule, paras. 10(c), 11 and Table 1.

- ↑ International Whaling Commission, Scientific Permit Whaling

- ↑ Appendix I to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES)

- ↑ 16 U.S.C. § 916

- ↑ 50 C.F.R. 224.101b

- ↑ 50 C.F.R. 226.215

- ↑ Angliss, R. P., and R. B. Outlaw. North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica): Eastern North Pacific Stock, NOAA-TM-AFSC-168, (revised 1/3/06)

- ↑ 50 C.F.R. 424.12b

- ↑ 73 F.R. 19003

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 73 F.R. 19005

- ↑ Recovery Plan for the North Atlantic right whale

- ↑ [3]

- ↑ Review: right whales in the North Atlantic and North Pacific Oceans

- ↑ Species at Risk Act Action Plan for Blue, Fin, Sei, and right whales, Balaenoptera musculus, B. physalus, B. borealis, and Eubalaena japonica in Pacific Canadian Waters

- ↑ Mitchell E (1979). "Comments on the magnitude of early catch of east Pacific gray whale (Eschrictius robustus)". Rep. int. Whal. Commn ": 29–307–14.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 Webb R (1988). On the Northwest, Commercial Whaling in the Pacific Northwest 1790–1967. Univ. Brit. Columbia Press.

- ↑ Brueggeman JJ, Newby T, and Grotefendt RA (1986). "Catch Records of the Twenty North Pacific right whales from Two Alaska Whaling Stations, 1917–39" (PDF). ARCTIC (1): 43–46. http://pubs.aina.ucalgary.ca/arctic/Arctic39-1-43.pdf.

- ↑ Clapham, P. (2006). "Disappearing right whales and the Secrets of Soviet Whaling". Quarterly Research Reports of the National Marine Mammal Laboratory, July–August 2006: 1. http://www.afsc.noaa.gov/Quarterly/jas2006/divrptsNMML1.htm.

External links

- NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service, Office of Protected Resources, North Pacific Right Whale

- National Marine Fisheries Service, Alaska Regional Office, North Pacific Right Whale Management in Alaska

- U.S. Marine Mammal Commission – North Pacific Right Whale

- National Marine Fisheries Service, National Marine Mammal Laboratory

- E. japonica – the World's Most Endangered Whale

- Fisheries & Oceans Canada – North Pacific Right Whale

- Fact sheet on right whales for kids

- Center for Biological Diversity – Right Whale page

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||